Mapp V Ohio 1961 Why It is Hard to Build Trust but Easy to Lose It

Mapp v. Ohio 367 U.S. 643 (1961)

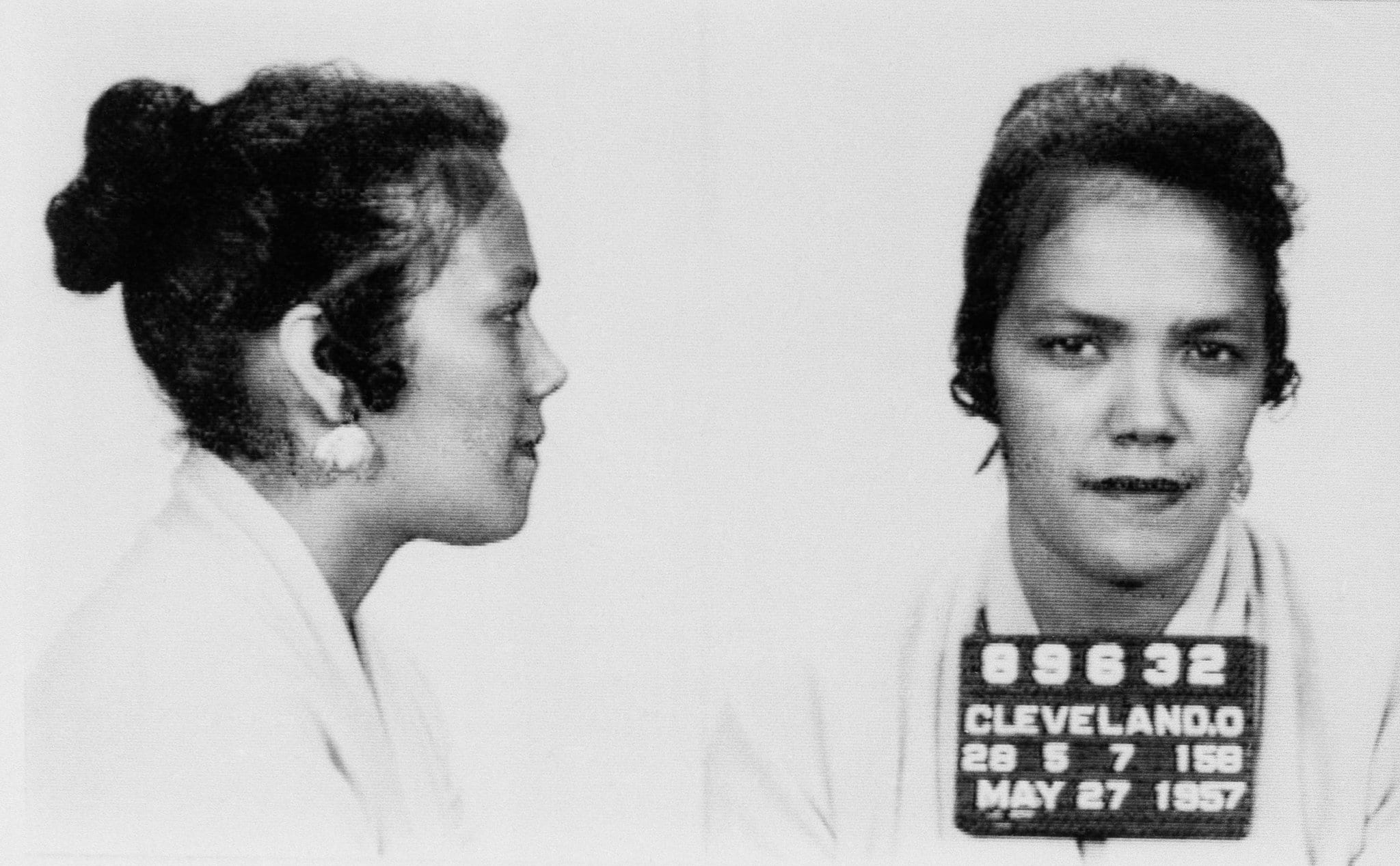

On May 23, 1957, police officers came to the home of Dollree Mapp based on information that a bombing-case suspect and betting equipment might be found there. The police requested access to the residence but were refused by Mapp. Mapp then refused a second request by the police to enter, at which point the police forced their way into the home. Mapp was handcuffed and a thorough search of the residence was conducted, despite the fact the police had no search warrant. As part of this search, obscene materials were found in a basement trunk, which provided the basis of Mapp's arrest. She was subsequently tried and convicted of being in possession of the obscene material, and her conviction was upheld by the Ohio Supreme Court. The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The case dealt with the application of what is known as the exclusionary rule. This rule holds that evidence obtained by an unlawful search and seizure in violation of the Fourth Amendment cannot be used against a defendant in court. The rule had come up in an earlier case, Wolf v. Colorado (1949), where the Supreme Court had limited the constitutional applicability of the exclusionary rule only to criminal federal prosecutions. This meant that the exclusionary rule did not apply to the states. Mapp v. Ohio would change this.

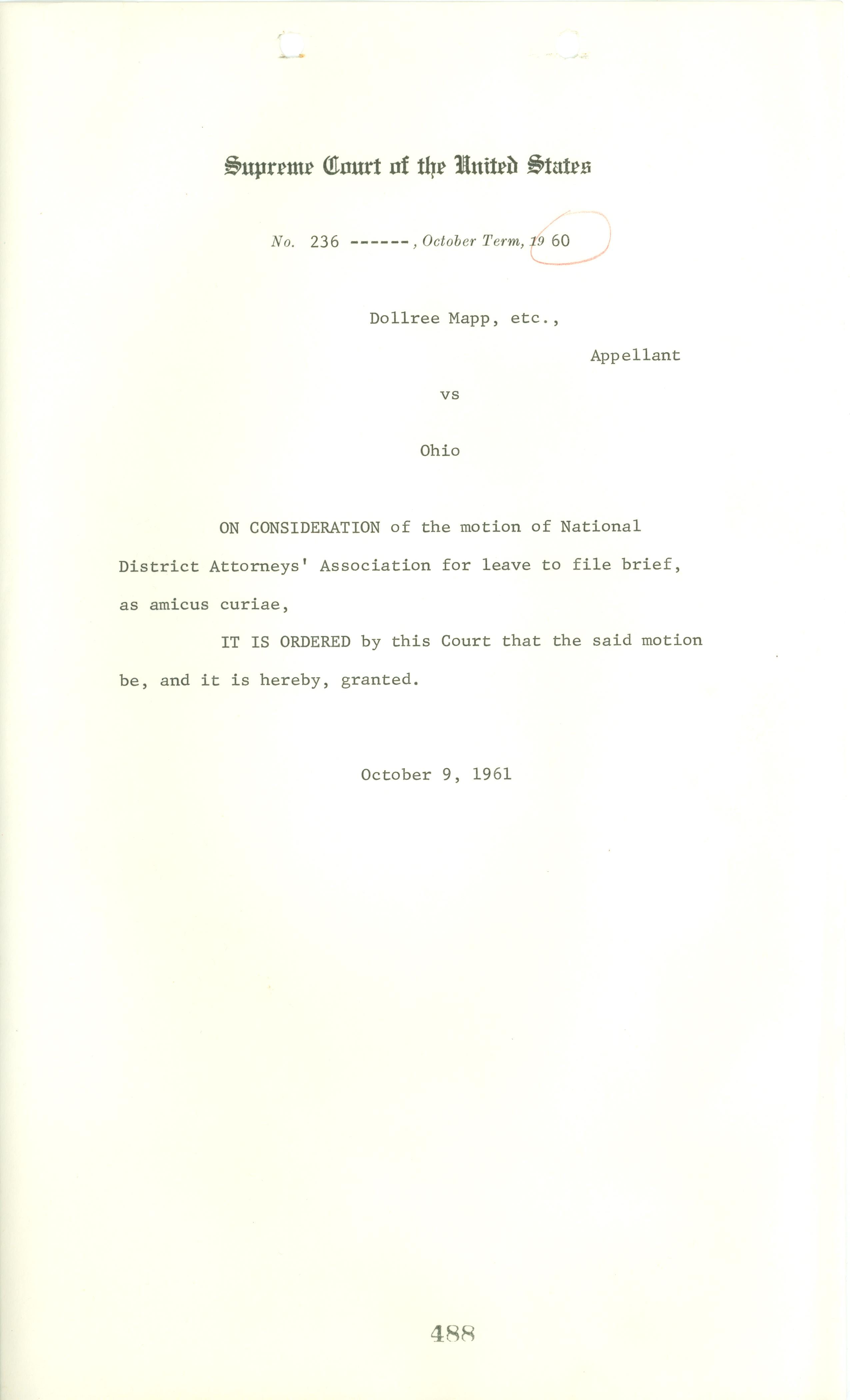

Although much of the proceedings dealt with First Amendment issues, such as the right to freedom of thought and expression and the due process clause under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court's opinion eventually revolved around the applicability of the exclusionary rule to states' conduct, an issue that was only briefly mentioned in an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief submitted by the ACLU. In its opinion, written by Justice Clark, the Court annexed the exclusionary rule to the Fourth Amendment's right to privacy and incorporated it into the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In doing so, the Court reversed its holding in Wolf that separated the exclusionary rule and the right to privacy, applying the exclusionary rule as binding upon all states. The majority concluded that the exclusionary rule, by removing the incentive to disregard the Fourth Amendment, constituted "the only effectively available way…to compel respect for the constitutional guarantee [of privacy]."

The dissenting opinion, written by Justice Harlan and joined by Justices Frankfurter and Whittaker, and, in part, by Justice Stewart, held that the case did not require reexamination of the Wolf decision. Instead, the case should have dealt more narrowly with the constitutionality of the Ohio obscenity law. Since the exclusionary rule was not a primary focus of the case, the Court should have waited until a case came before it that did raise the exclusionary rule as its central issue. The occasion, Harlan wrote, "which the Court has taken here is in the context of a case where the question was briefed not at all and argued only extremely tangentially."

The exclusionary rule exists to deter and prevent law enforcement from engaging in searches that violate the Fourth Amendment because of the lack of a warrant or probable cause. If police, for example, search someone's home without a warrant, any incriminating evidence found as a result of that search would be held inadmissible against a defendant. Moreover, if evidence of other crimes was found as part of an unconstitutional search, that evidence would be inadmissible as well because it would be considered "fruit of the poisoned tree."

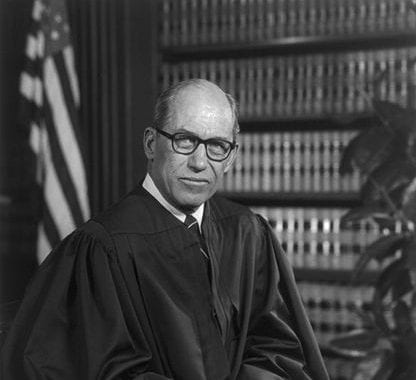

Since the Mapp decision, the exclusionary rule has come under both intense criticism and attack. Opponents argue that its effect is to exclude evidence from the courts that is needed to ensure justice. It also hinders the police in performing their duties and it can absolve a guilty defendant based on a "technicality." Even more intense criticism has come from members of the Court. Justice Burger, in his dissent in Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents (1971), called for the exclusionary rule's elimination and an end to what he called the "universal capital punishment we inflict on all evidence when police error is shown in its acquisition." Instead of the exclusionary rule, Burger called on Congress to enact legislation that would waive sovereign immunity as to the illegal acts of law enforcement officials committed in the course of their duties, along with other measures that would bring accountability for violations of the Fourth Amendment. Evidence, however, should be admitted once it is obtained.

While the Court has never gone as far as Burger would have liked in eliminating the exclusionary rule, it has come to recognize a "good faith" exception to it. This exception can be found in cases such as United States v. Leon (1984), Arizona v. Evans (1995), Herring v. United States (2009), and Heien v. North Carolina (2014). In these cases, the Court has held that the exclusionary rule should not be applied in instances where there was a reasonable belief that evidence was obtained in a way that was consistent with the Fourth Amendment. In the words of Justice White in Leon, "the exclusionary rule cannot be expected, and should not be applied, to deter objectively reasonable law enforcement activity . . . this is particularly true, we believe, when an officer acting in objective good faith has obtained a search warrant from a judge or magistrate and acted within its scope."

Thus, Mapp v. Ohio continues to exert a substantial influence on both law enforcement and courts throughout the United States, and debate continues over the existence and scope of the exclusionary rule. While it is unlikely these debates will be resolved anytime soon, it is clear 60 years later, that Mapp has extended the protection of privacy for citizens against state intrusion.

bergeronkelin1954.blogspot.com

Source: https://teachingamericanhistory.org/blog/mapp-v-ohio-60-years-later/

0 Response to "Mapp V Ohio 1961 Why It is Hard to Build Trust but Easy to Lose It"

Post a Comment